The repairman had failed to follow instructions for shutting down the arm before he entered the workspace. At the Kawasaki Heavy Industries plant in Akashi, a malfunctioning robotic arm pushed a repairman against a gearwheel-milling machine, which crushed him to death. I have a yellowed clipping dated December 9, 1981, from the Philadelphia Inquirer - not the National Enquirer - with the headline “Robot killed repair man, Japan reports.” The first robot homicide was committed in 1981, according to my files. My view is that for quite some time the mens rea most relevant will be of some power-hungry human villain using AI, rather than of some conscious, autonomous, and evil AI system itself … but who knows?Įveryone who thinks about ethics, is concerned about the future dangers of AI, and wants to support efforts to keep us all safe should read on… He focuses on the central concept of mens rea, or “guilty mind,” asking how we would ever know when a computer would be so self-aware as to satisfy the legal criterion to make him (it) guilty of murder. His chapter, published nearly 25 years ago in “ HAL’s Legacy,” a collection of writings that explore HAL’s tremendous influence on the research and design of intelligent machines, remains an indispensable introduction to the thorny problems of “murdering” by computers and the “murder” of computers. Stork is the editor of “ HAL’s Legacy,” from which Daniel Dennett’s essay is culled.Īt the philosophical center of these developments are the notions of responsibility and culpability, or as philosopher Daniel Dennett asks, “Did HAL commit murder?” There are few philosophers as knowledgeable and insightful about these fascinating problems, and who write as clearly and directly. The most pressing dangers of AI will be due to its deliberate misuse for purely personal or “human” ends.ĭavid G. Then too are the “sci fi” dangers of AI run amok. The naive bromides of an invisible economic hand shepherding “retrained workers” into alternative and new classes of jobs and such are dangerously overoptimistic. Indeed, future developments in AI pose profound challenges, first and foremost to our economy, by automating away millions of jobs in manufacturing, food service, retail sales, legal services, and even medical diagnosis. Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, Sam Harris, and many other leading AI researchers have sounded the alarm: Unchecked, they say, AI may progress beyond our control and pose significant dangers to society.Īnd what about the converse: humans “killing” future computers by disconnection? When astronauts Frank and Dave retreat to a pod to discuss HAL’s apparent malfunctions and whether they should disconnect him, Dave imagines HAL’s views and says: “Well I don’t know what he’d think about it.” Will it be ethical - not merely disturbing - to disconnect (“kill”) a conversational elder-care robot from the bedside of a lonely senior citizen?

AI-powered bots, meanwhile, are infecting networks and influencing national elections.

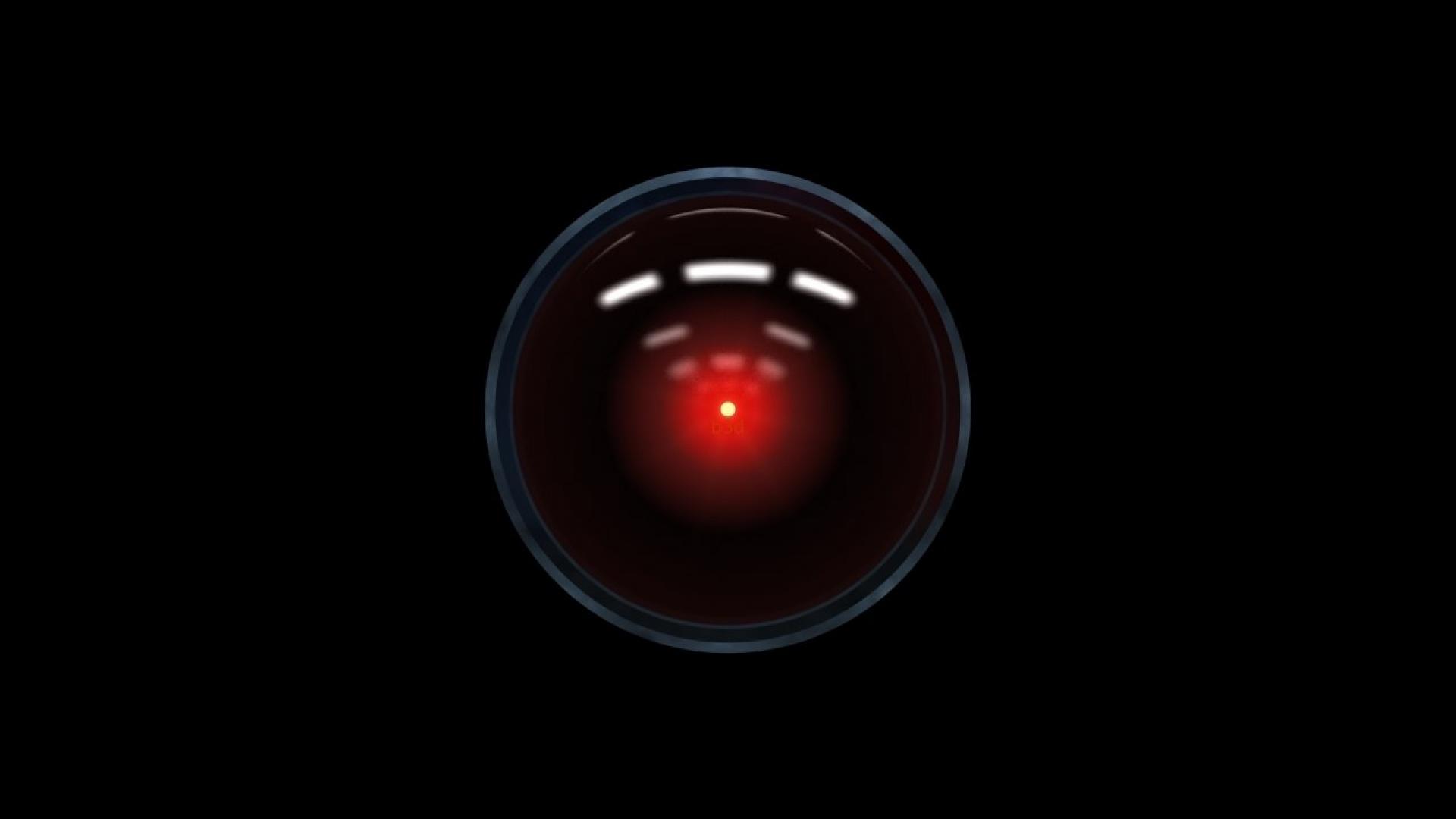

In the past few years experimental autonomous cars have led to the death of pedestrians and passengers alike. But three iconic scenes - HAL’s silent murder of astronaut Frank Poole in the vacuum of outer space, HAL’s silent medical murder of the three hibernating crewmen, and the poignant sorrowful “death” of HAL - prompted deeper reflection, this time about the ethical conundrums of murder by a machine and of a machine. Clarke, and their team of expert filmmakers.Īs with each viewing, I discovered or appreciated new details. The fact that this masterpiece remains on nearly every relevant list of “top ten films” and is shown and discussed over a half-century after its 1968 release is a testament to the cultural achievement of its director Stanley Kubrick, writer Arthur C.

Last month at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art I saw “2001: A Space Odyssey” on the big screen for my 47th time. BeeLine Reader uses subtle color gradients to help you read more efficiently.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)